It has long been said that the private pilot certificate is a “license to learn” as it is the foundation of a person’s flying career.

To take advantage of the so-called pilot shortage, many schools and independent instructors have adopted the check-the-box style of instruction, and when the applicant has completed the tasks listed in FAR 61.109 and passed their knowledge test, they are sent to the designated pilot examiner (DPE) for their check ride. According to examiners across the country, there is a trend of only half of the applicants passing the check ride on the first try—despite having logged the experience, they don’t know the material. And there are others who don’t meet the experience requirements for the certificate, which is often found during a review of the applicant’s logbook and should have been caught much earlier.

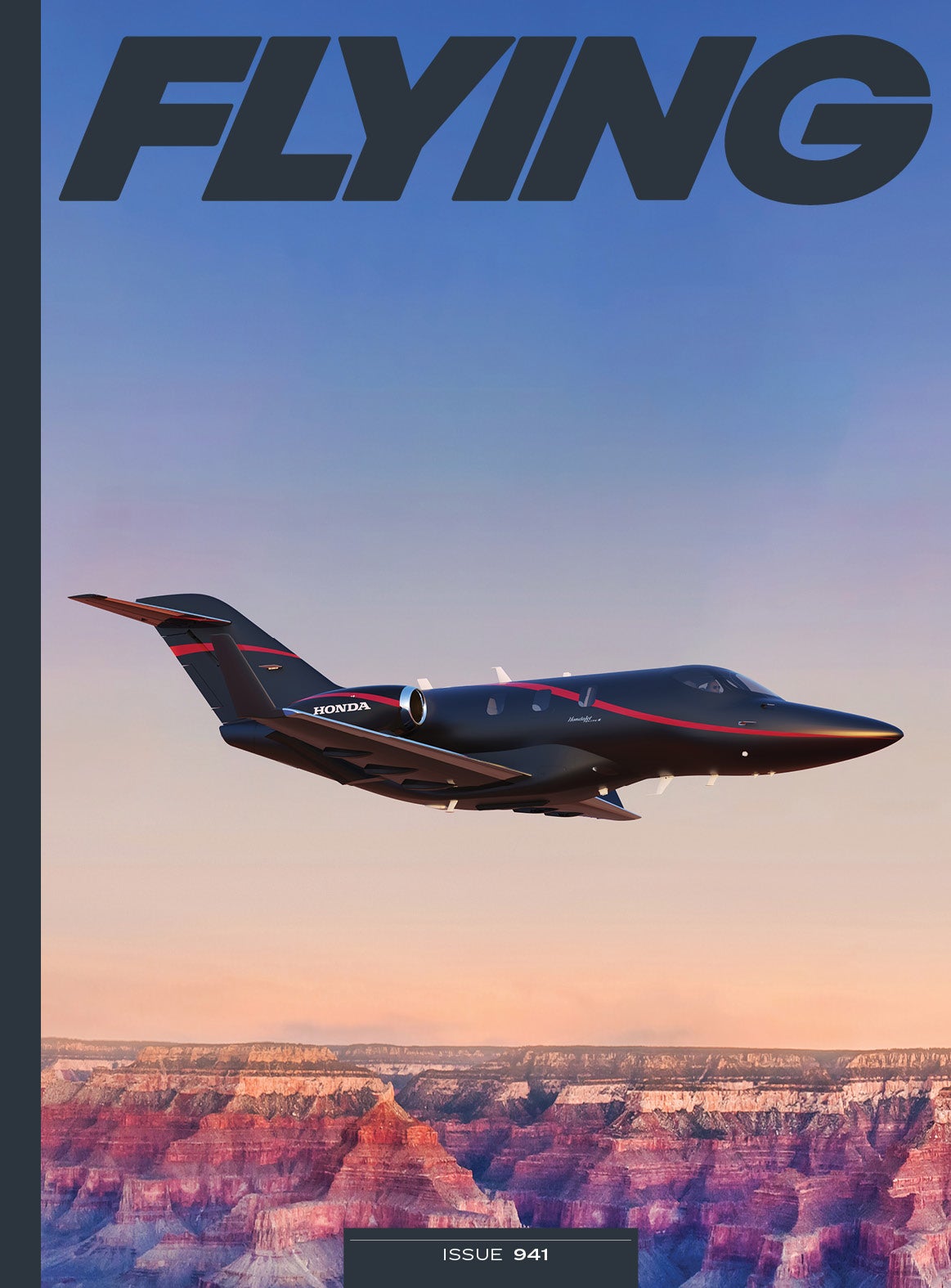

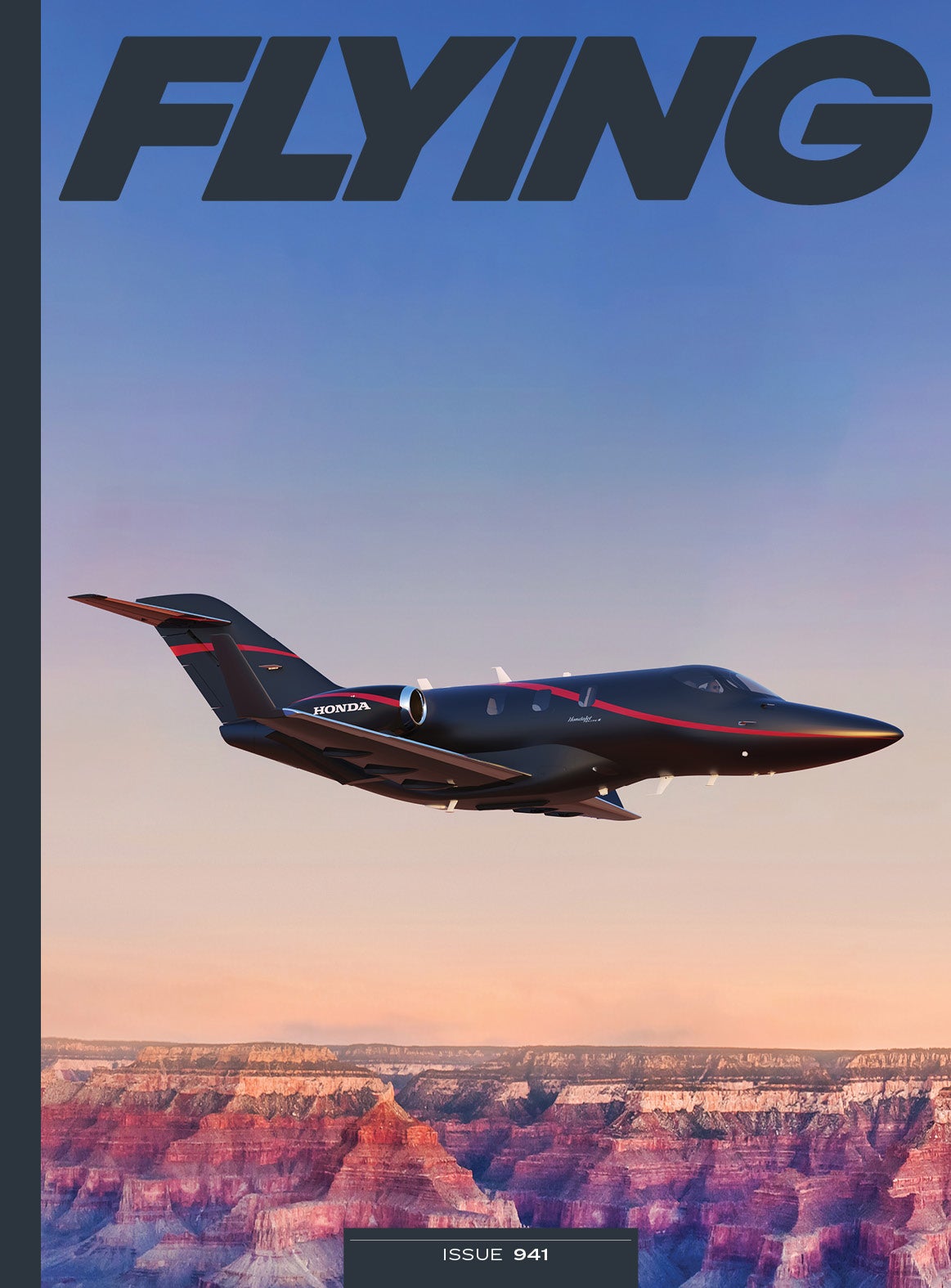

If you’re not already a subscriber, what are you waiting for? Subscribe today to get the issue as soon as it is released in either Print or Digital formats.

Featured

I am not a DPE, but for several years I have been a check pilot providing mock check rides for applicants at the request of their CFIs.

The culture of many flight schools and some independent instructors is “train them quickly.” As such, many applicants go into their check rides with minimum experience and abilities because they were trained by an instructor with minimum experience and abilities. This can lead to blind spots and soft spots in the applicant’s skills and knowledge. FLYING offers a few tips to help you avoid this.

Use a Syllabus

Preparation for a successful check ride begins with the use of a syllabus. It provides guidance and a clear path to certification as each lesson has competition standards. You know when you have done well if you meet these standards. Required in a Part 141 environment, highly recommended in Part 61, have it with you for all lessons be they in the air, in the classroom, or AATD.

If your instructor wasn’t trained using a syllabus, they may be reluctant to use one. Insist on it.

When a Part 61 learner says, “I think my instructor is using one,” it makes me want to cry out like someone just blew up Alderaan. If you haven’t seen it, or if you don’t have a copy of it during the lesson, you’re not using one.

Use the ACS from Day One

Utilize the private pilot airman certification standards (ACS) from the get-go. These are the minimum standards the applicant must meet in order to achieve their certificate. To put it into perspective, meeting the metrics of the ACS is like getting a “C” in a class. C grades may still result in a degree, but strive to do better.

For example, if the ACS states that during takeoff the applicant will “maintain VX/VY as appropriate +10/-5 knots to a safe maneuvering attitude,” focus on nailing the airspeed. Every time. If the POH says VX is 67 knots, fly at 67 knots.

While it is unlikely that you will meet the ACS metrics the first time you fly a maneuver or demonstrate knowledge, it is much easier to train to the metric rather than trying to clean up a sloppy performance later. Sadly, many private pilot applicants are told they don’t “need the ACS yet” when they begin their training. Establishing a criteria for what are acceptable standards from the first lesson can help both the learner and CFI stay on track and keep the learner engaged in the process.

CFIs: Remember many learners drop out of training because they don’t know what is expected of them or if they are doing it right. The ACS, coupled with the syllabus, answers these questions.

Aim High

The four levels of learning are rote, understanding, application, and correlation. Aim for correlation, and understand the what, why, and when of a topic. So, for example, if you are asked to provide a scenario when VX is appropriate, be able to answer the when and the why, such as “short field takeoff technique is appropriate when there is an obstacle off the departure end of the runway.”

Application, correlation, and understanding are critical when it comes to aircraft systems. You can tell when an applicant is responding by rote, such as if the pilot of a fuel-injected aircraft suggests that an uncommanded loss of engine power they experienced in flight is probably because of “carburetor” icing.

Update Your Logbook

There’s a running joke at flight schools that you know when some is getting ready for a check ride because they are playing catch-up, totaling their logbook. Doing this in a rush is when mistakes happen. It is much better to total up page by page, checking the math twice before you commit it to ink.

All instruction received should be logged, per FAR 61.51: flying, AATD, and ground. It’s all valuable. Periodically go through your logbook, noting your experience acquired and the requirements for private pilot certification as stated in FAR 61.109.

Double-check that you both have the experience and that it is properly logged, as incorrectly logged experience can nullify a check ride before it begins.

For example, logging “night flight” on a line means the applicant flew at night. The night requirement for the private pilot candidate is more than “three hours of night.” There is also a cross-country and 10 takeoffs and landings with the caveat that the landings must be full stop. Make sure your logbook reflects this.

Your instructor is responsible for making sure you have all the endorsements necessary for the check ride. The examiner will look for the TSA endorsement, first solo, initial cross-country, subsequent solo endorsements, additional cross-country flights, satisfactory aeronautical knowledge, additional training in areas found deficient on the knowledge test, three hours of check ride prep within two calendar months in preparation for the practical test, and flight proficiency for the practical test.

A list of the endorsements and appropriate language can be found in Advisory Circular 61-65. Although your logbook may have preprinted endorsements, the savvy CFIs will refer to the language in the AC and defer to it.

Make sure your solo endorsement is current as well.

Prep for the Knowledge Test

The minimum passing score is 70—but the better you do on the test, the easier the check ride can be.

When the examiner receives your application (filed electronically with the help of your instructor), they review your knowledge test score to develop a plan of action for the check ride. A wrong answer is considered an “area found deficient,” and that is often where the oral exam begins.

The test codes are found in the ACS, so you should know where your soft spots are.

You may have only missed one question in the area— like aircraft performance—but your CFI should drill you on it, as the DPE will be using your knowledge exam results to tailor the check ride.

Use Your Reference Material

While there is an awful lot of information for a pilot to remember, one of the most important skills you can have is knowing where to look up something to verify the information. The VFR sectional has a legend, so you don’t have to guess at what kind of airspace that is. Chapter 3 in the AIM has details on dimensions of airspace, cloud clearances, and visibility.

Whether electronic or paper, there are certain things you want tabbed to make it easier to find— for example, in the FAR/AIM Part 1 definitions, 61.109, aeronautical experience required for a private pilot, Chapters 3 and 7 of the AIM (Airspace and Meteorology), etc.

A good pilot knows how to use these resources to look up the information and takes the initiative to do this. If you cannot or will not do this, flying is not for you.

Verify the Aircraft Paperwork

Before a check ride can happen, the applicant and DPE must go through the aircraft maintenance logbook to make sure it meets the airworthiness requirements. Sadly, the check ride is often the first time some applicants have seen the logbooks for the aircraft.

Avoid this situation by sitting down with your CFI and going through the logbooks to verify the aircraft is airworthy, using the acronym AAV1ATE as your guide (ADs complied with, annual inspections, VOR every 30 days, 100-hour, altimeter/pitot static system every 24 calendar months, transponder every 24 calendar months, ELT check). Before your check ride, find the

most recent inspections and put a Post-it note on them so you can easily find them to show the examiner.

Make sure the aircraft’s dispatch paperwork, such as the weight and balance sheet, is up to date.

Study Multiple Nav Modes

The flying portion of the check ride has the applicant flying a preplanned cross-country flight. The examiner will supply the destination. You will fly one, perhaps two legs of it, but fill out the navlog completely, including estimated time to top of climb, runway distance required, radio frequencies, etc.

If the aircraft has a GPS, know how to program it—and, more importantly, how to fly if the GPS—or ForeFlight if using your iPad—“fails.” And it likely will, as the examiner will fail them during the flight to see if you can navigate by pilotage and ded reckoning. Be sure you can. Be able to read a VFR sectional.

Have a current sectional and chart supplement. If you have a dated version of the FAR/AIM in hard copy (paper), have an electronic version at your fingertips so you can look something up if needed. The printed version goes out of date quickly, which is why many pilots prefer the e-version.

Take a Mock Ride

Insist on a mock check ride with an instructor you don’t usually fly with—preferably one with a lot of experience with the DPE you will be testing with. They probably have a stack of debriefs from their learners containing questions the DPE asked in the past. These are called gouges, and while they are helpful, don’t bother to memorize them as each DPE will create a plan of action individualized to the applicant.

The best pilots go into their check rides overprepared and come out the other side with a smile on their face and a certificate in their pocket.

This column first appeared in the March 2024/Issue 946 of FLYING’s print edition.